Amid the global stock market and policy turmoil caused by Trump’s rollout - and subsequent 90-day pause of reciprocal tariffs - the initial consensus was that its impact on India will be relatively muted. Chinese goods will incur a tariff rate of up to 145per cent , whereas goods from India and other countries will now attract a flat 10per cent rate. The automobiles and auto parts sector are exempt from reciprocal tariffs, but will have a separate 25per cent tariff rate.

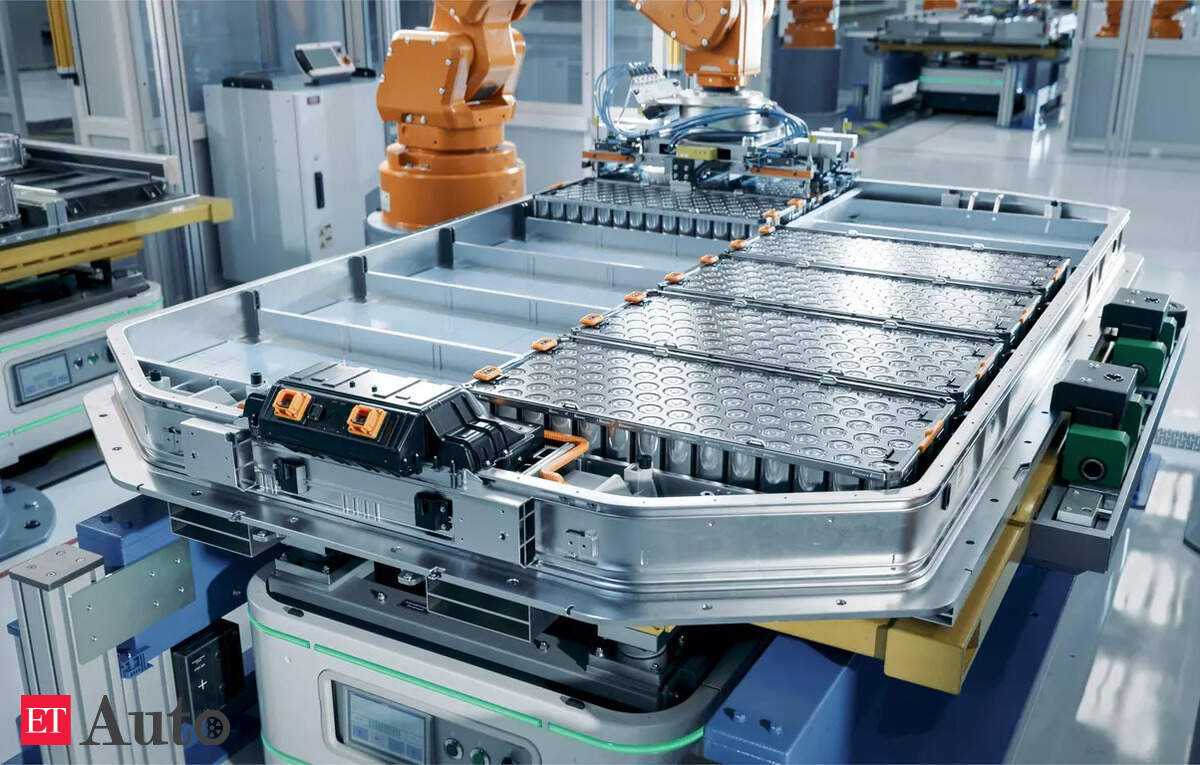

However, with China recently placing restrictions on exports of rare earths and key technologies, it could have a potential impact on India’s battery ecosystem. Given the implications of these tariffs in reshaping global supply chains, India’s electric vehicle (EV) and battery industry needs to respond quickly, both to remain competitive and capitalize on these emerging shifts.

With the US market becoming increasingly difficult to access for foreign companies, and the Trump administration’s priorities shifting away from clean transport, Asian battery giants are likely to pivot towards the rest of the world - including India, given the overcapacity across the battery supply chain. Given that global cell companies are increasingly building manufacturing facilities in Southeast Asia, there is likely to be healthy competition between Indian and SEA cell manufacturers since India has an existing Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement (CECA) with the ASEAN region. Companies in South Korea also benefit from the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) signed between both countries. Both of these agreements ensure zero duty lithium-ion cell imports into India.

With India’s battery manufacturing industry still at a nascent stage, it is crucial for the government and private sector to collaborate and ensure that the industry continues to grow, and supports new jobs, exports and domestic value creation.

Learn from high-profile Global North failures by forming JVs with Asian battery giants.

There have been high-profile failures recently in the battery cell industry, such as Northvolt in Europe and Britishvolt in the UK, which filed for bankruptcy protection in 2024 and 2023 respectively. Northvolt had raised US $15 billion and had supply agreements with major OEMs, such as Volkswagen and BMW, but was still unable to scale up production. These failures highlight the technological and economic complexity faced by companies other than some of those in China, South Korea and Japan in manufacturing cost-efficient and reliable battery cells.

The main takeaways from the Northvolt debacle was its lack of focus towards core business segments and aggressive geographical expansion plans without building the right foundation, leading to overstretched resources, labor shortages and operational inefficiencies.

A study from Volta Foundation found that the fastest and most reliable way to set up and scale battery cell manufacturing is through joint-venture partnerships with leading global companies. Given the recent thaw in India-China relations, New Delhi should encourage partnerships between domestic companies and Asian battery companies that can support skills and technology transfer, as well as line automation and a qualified, competitive and reliable supply chain.

These JVs should be ideally majority owned by the domestic company to ensure technology transfer and the development of local know how. The EU has been mulling over new guidelines requiring international companies to transfer intellectual property and technology in return for accessing subsidies to set up battery plants on the continent.

Targeted public support can play a key role

The Indian government has implemented several policies that helped kick start battery cell manufacturing in India. The Cabinet approved the production-linked incentive scheme for advanced chemistry cell batteries (PLI-ACC) in May 2021, allocating ₹18,100 crore to create a manufacturing capacity of 50 GWh. However, progress has been mixed, with a recent media report claiming that only ₹24 crores has been disbursed so far to PLI ACC winners, less than 1per cent of the estimated ₹2700 crores which should have been spent by now.India could potentially dilute some of the stringent localization requirements under the PLI-ACC scheme, which mandate a beneficiary must achieve a domestic value addition of at least 25per cent within two years and 60per cent domestic value addition within five years.

Given the lack of a well-developed battery ecosystem, it will be crucial to come up with a realistic localization requirement and speed up fund disbursements given the heavy capex requirements of the industry. It could also extend the PLI benefits to a more diversified ecosystem of companies, particularly in the midstream segment, such as cathode and anode manufacturers.

Encouragingly, the government has exempted import duties on raw materials and 35 capital goods used in battery cell manufacturing in the recent budget. It has also permitted the duty free import of li-ion battery scrap, which is an important step to promote refining capabilities in the country. This should help domestic cell companies become more competitive and get access to the entire value chain.

The Indian government can go further by playing the role of an offtaker and seed initial demand by incentivizing the use of Made in India li-ion cells and batteries in specific use cases controlled or influenced by it . Some examples can be electric buses or BESS systems, which will ensure guaranteed demand for domestic battery cell manufacturing companies in the future.

Furthermore, the government could incentivize faster EV deployment to create a larger market for domestic cell companies. EVs accounted for just under 50per cent of new car sales in China in CY 2024, which is the world’s largest car market. The penetration level in Europe was 23per cent while the US’s was around 10per cent . Total EV sales penetration in India across vehicle categories reached 7.8 per cent in FY 2024-25. Without strong consumer demand, even the most well thought-out plans on manufacturing and technologies will not get traction.

While the Indian government has rolled out the PM E-Drive scheme to support EV deployment, it could consider supply-side policies, such as ZEV mandates, which require automakers to sell a certain percentage of EVs each year relative to their total sales, and played a crucial role in driving EV uptake in China.

Increased manufacturing efficiency will be key for the private sector Indian li-ion cell companies must focus on building their manufacturing processes so as to reach a 95per cent + efficiency level within the first few years, before focusing on supply chain localization. Their initial focus should be to reduce the variability in the processes and supply chains of their international technology partner and the lines coming up in India.

Cell companies should also work closely with automotive OEMs by receiving early feedback on cell specifications and shortening the turnaround time for cell qualification.

The increase in tariffs by the Trump administration shouldn’t be seen as one-off, or limited only to the US. Developing countries, such as India, will need to navigate growing trade barriers from advanced economies on the one hand, and China’s dominance in manufacturing batteries and clean energy technologies on the other. With a large market and innovative startups, India is well placed – how adeptly it is able to unlock this potential will determine the future of its cell and battery industry.

(Disclaimer- Siddharth Goel works as an Independent Consultant specializing in electric mobility and battery supply chains. Dev Ashish Aneja works as the head of cell supply chain at Ather Energy. The opinions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of ETAuto.)

Comments (0)